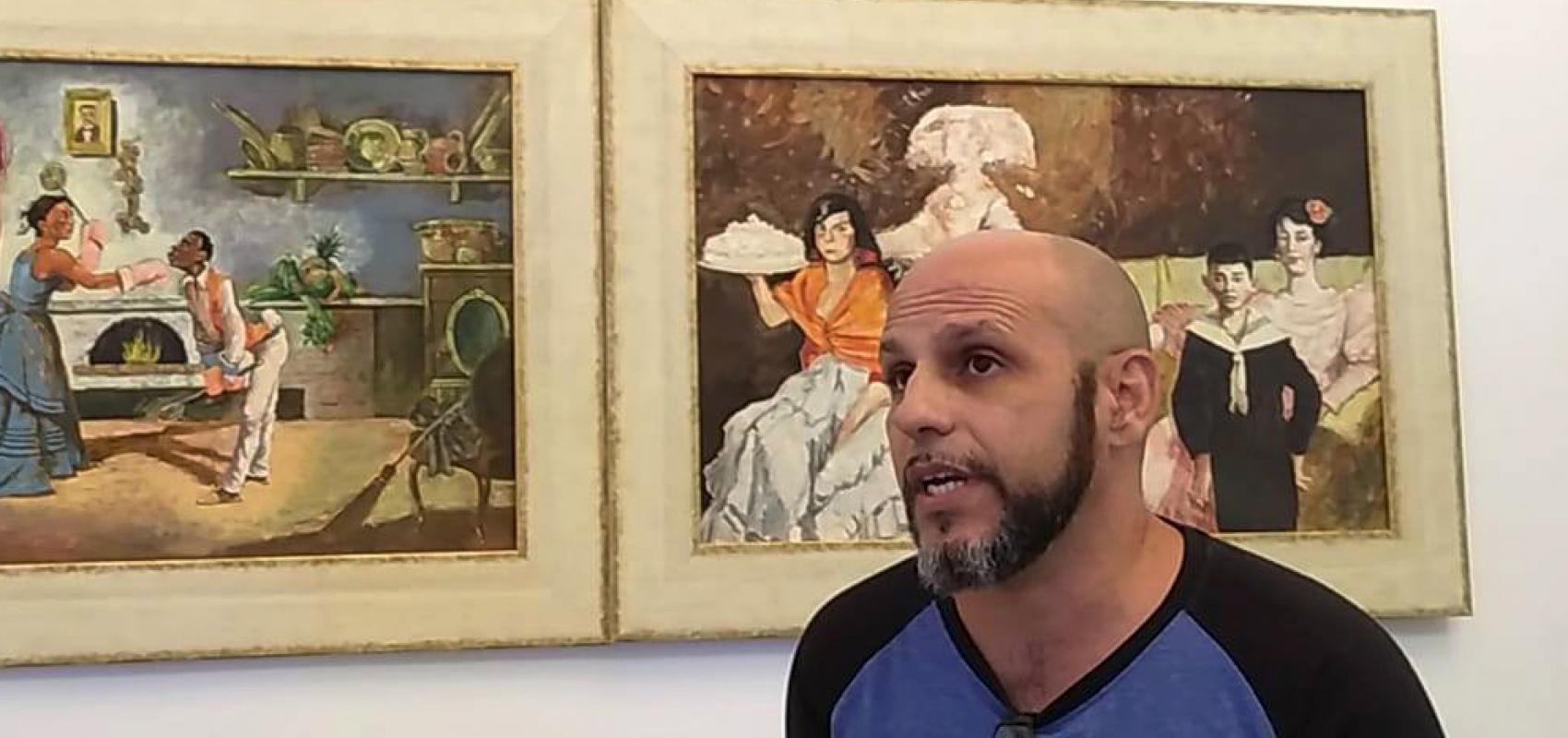

For simple mortals, yes, those who don't seem to care about the footprints of time, accessing the minds of artists is very much like conquering glory for a few minutes. In the case of Douglas Perez Castro, the sensation remains for a while longer, because he is a natural conversationalist, accessible, without many hiding places for sincerity.

Before the painting took possession of his thought, Perez Castro assures, in an exclusive interview with Maxima, his intentions to be a writer. That is why it is not surprising the precision with which he describes his works by means of small texts in social networks, in such a way that he invites Internet users to discover his creative pulse. Without speaking, he convinces from a rigorous approach to the history of Cuba, among other passions where reality shudders by its very figuration.

From now on, Douglas Perez Castro has the floor.

Why customary painting as one of his discourses in art?

For many years I have carefully studied each of these proposals at an image level. I have found a propitious scenario to comment on the Cuban reality, the reality that surrounds me and, in a particular way, myself as a subject in that context, in addition to making an approximation signifying the problems that we have to face daily.

Within my line of work this is part of an investigation that I have been doing about postcolonial thought and a little is linked to the practice of pictorial discourse, with common referents in the context of Cuban plastic arts. I am basically referring to the work of the artist Víctor Patricio de Landaluce and to the French and Spanish engravers of the 19th century, which the Museum has a vast collection.

Along with costumbrista painting, intentional doses of humor are also observed. How much does Douglas Perez Castro look like his characters?

I'm not going to deny that it's part of my personality. It's another studied facet, to which I've been deeply rooted. My father was a cartoonist, Douglas Nelson, recognized in the center of the country, founder of the humorous weekly Melaito, in Villa Clara.

I grew up in a context where seeing my father drawing graphic jokes, both for the provincial press and for this weekly, was usual. I was also struck by his character, because humorists also have a way of activating certain contents when communicating that were common to me. Somehow that appears in my work.

On the other hand, costumbrismo has a line very close to that of choteo, that critical gracejo of seeing tragicomic situations in different modes of expression. We have a tradition based on the development inherited from the past. Many elements that today are seen as distinctive, the case of machismo, gender conflicts such as racism, are lagging behind the same underdeveloped condition of this nation. Basically it is poured in each of these works, in the titles, in the compositions, in the comments per se that one finds in the street.

In order to achieve this fidelity, how much did he have to nourish himself with references of Cuban culture?

I made a careful approach to literature and history. One of the lines of work parallel to the discourse of the manipulation of traditionalism is a painting essay that I have done for years, where the thematic axis is sugar and its influence on culture.

I had to read El Ingenio, of Manuel Moreno Frajinals, African folk music from Cuba, written by Fernando Ortiz, as well as the work of writers who coexisted at the best moment in the development of sugar in Cuba, such as Frederika Bremer (who stayed 100 days in Havana) or the chronicles of Abel Abot, as well as The Dark Jungle, by Abelardo Estorino. All that has been nutritional sap for me.

The atmospheres are also recreated with great care in painting. How does the artist conceive them?

I propose not only to entertain the narrative discourse, but also to investigate, at an aesthetic level, the characteristics of that painting, that is, what academicism meant in the Cuban school of painting of the 19th century, based on studies from the processual point of view, essential for a work of this type.

There are two ways of activating content in the pastiche: one is from that quotation, which can be the characters and characters that identify the process, and another at a symbolic level that constitutes the aesthetics on which the paintings are built. I have had to be very respectful, the works are made in oil, following a three-layer methodology, where there are glazes and a way of understanding physical time that is very much in tune with historical tempo.

Contemporaneity has awakened a dynamic which makes physical time very short, dynamic. In a work like this I have tried to feed the romantic myth of the artist, who is in a workshop devoting long hours to build a work, and where the idea of uniqueness is in the ability to feed those original shortcomings. Until the spectator wakes up, why not, a certain nostalgia that can support that discourse linked to the study of history and tradition.

On the other hand, in his works such as Picazzo, Transgenic or Trojan there is a completely different figuration. I stop at The Great Banana Republic, the piece that identifies his profile in Maxima. Why the banana as a pondering visual resource?

This work belongs to the Pictopía series. I searched popular culture for the tradition of narrating progress or the future, which can be found in science fiction illustrations. There is a vast tradition of an imaginary constructed from exaggerating or saturating the sensations of development or evolution to higher stages. On that basis I built that space of neologism, if you will, which is the union of the term picto (that comes from image) with utopia.

The Great Banana Republic is one of those works and the theme is to address the choteo, the clichés that have been understood as representative of certain cultural phenomena, such as underdevelopment. For a long time the banana was used as a derogatory symbol to denote countries or societies linked to rudimentary economic processes, so it becomes a meaning of poverty, with respect to the aspirations that individuals have in those contexts.

This work was constructed from a postcard that I encountered in the Hollywood hills. I built this Havana where the Havana poster is read, similar to the poster that Hollywood points out in the hills of Los Angeles, but it is a retruecano of words because what it actually says is Habanana.

Rather, it is a metaphor for that discourse that constantly tries to saturate us, with which we are a perfect society and where development is within reach. The painting is that, a postcard of a supposed Havana of development where lights, dynamics and movement are constitutive of happiness, of consumption, of symbols, of joy and that leads the individual to consider a plan for a romantic, beautiful future.

SEE ALL THE WORKS OF THIS ARTIST